“Masculinity“

Moore, E. Al-Tariq. “Masculinity.” Ralph Ellison In Context, Cambridge UP, Cambridge, UK, 2021, pp. 147–156.

Scholarship on Invisible Man has long acknowledged the importance of putting Ralph Ellison’s letters, speeches, and essays in conversation with the novel in order to fully understand its politics on race, gender, and sexuality. These constructs reveal themselves in the intersections at work in his character constructions and his views of the world in which they exist. Though race and gender are often discussed separately with regard to the novel, the critical manner in which they inform one another is of key importance. Perhaps one of the most significant narrative moments relative to this concern is excluded from the 1952 text, but exists among Ellison’s archived draft materials. For reasons yet unknown, he excluded a chapter containing a black queer character named Woodridge who, in that iteration of Invisible Man, has a tremendous impact on the protagonist’s social awakening and the shaping of his academic and worldviews. While we are uncertain as to whether Ellison draws on a professor he would have had contact with during his years at Tuskegee to craft Woodridge, it is possible.[1] In this chapter, I explore the implied gender politics signified by Woodridge and how they are relevant to discussions of Ellison’s novelistic distributions of racial agency, particularly as it regards black men and women, and the queer body. This under-discussed aspect of the novel is crucial to questions of precisely who Ellison, via Invisible Man, imagines accomplishing the goal of racial uplift, what aspects of their personas and identities qualify them to do so, and how we might interpret the marginal positions held by black women.

The redacted Woodridge chapter provides an interesting point of entry into Ellison’s thinking about black sexuality, namely black male homosexuality. Though it is unclear why the published novel excludes the full chapter, it is nevertheless a gateway that allows us to understand Ellison’s authorial liberty. It is possible that the explanation for the exclusion of the chapter may be of less importance than what it contains. Though his letters tell us that he was personally tolerant and accepting of homosexuality, they neither say much regarding the complexity of his thoughts relative to the broader social situation of black queer subjects, nor do they tell us his sentiments regarding the role of the black homosexual in the collective struggle for racial equality. [2]

Because the novel is so heavily invested in the development of black male leadership, and conceiving reform through a lens of radical masculine action, the characterization of Woodridge in the unpublished draft sets up a vexed quagmire of gender non-conformity and black homosexuality in juxtaposition to traditional notions of black nationalism that often exclude (or at the very least marginalize) women and those outside the boundaries of heteronormativity. While Ellison presents Woodridge as a stereotypical caricature of a black queer man, he also expresses latent ideas regarding gender performance, and the sociopolitical limitations placed upon those whose expressivities diverge from hard-lined societal expectations. Through Woodridge, Ellison gets at the consequences of difference and the pervasive myopia that often presides over constructions of blackness. He prominently conceptualizes his most potent agentive black figurations as both male and heterosexual, eliding any acknowledgement of black male homosexuality and the feminine as racially agentive embodiments.

II

Woodridge, as he is conceived in the unpublished drafts, is a young literature professor and champion debate team coach at the college Invisible attends. He is identified as “. . . the teacher mentioned when there was a question of ideas and scholarship. He was the nearest symbol of the intellectual to be found on the campus.” Despite his scholarly superiority, he was also considered to be a threat. Upon meeting “Invisible,” he asks, “Haven’t you heard that I was a dangerous, wicked man?”; he replies, “No, but I heard that you were the smartest teacher on the campus.”[3] The use of “dangerous” and “wicked” seems to be a weaponizing of Woodridge’s character by Ellison when realizing his queerness.

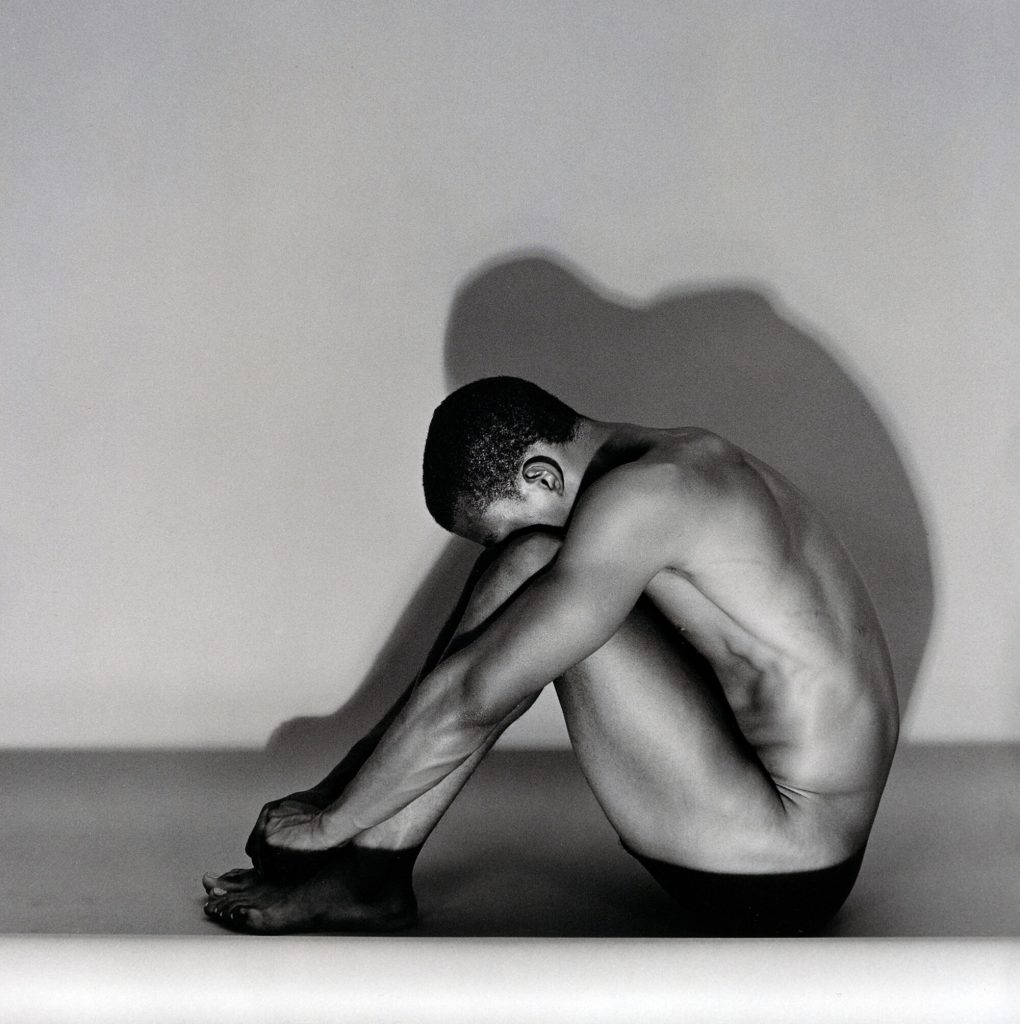

In the redacted chapter, Invisible observes that “[t]here was something bright, almost feminine about [Woodridge’s] room”; he is also “surprised” that Woodridge wears a “wine red dressing robe” and “. . . the end of a woman’s stocking . . . stretched over his head to keep his hair in place.” Likewise, “[h]e pointed to a chest on one end of which there stood a nude male torso and on the other an ugly primitive African statue.”[4] These signifiers of femininity and serve to mark Woodridge as queer and give credence to certain “rumors” that persisted about him throughout the campus, rumors that may concern his sexuality.[5]

One reading of Woodridge’s weaponization by Ellison could be that queer blackness ostensibly works counter to black cultural and political aims. Woodridge’s status as an instructor endows him with the feared capacity to indoctrinate students with ideas that complicate the goals of the race and accepted gender norms. More specifically, if the overarching goal of the race is to gain greater sociopolitical power, designating Woodridge as “dangerous” and “wicked” suggests his sexuality is a form of disempowerment. The most potent form of empowered blackness is revered as not only masculine, but also heterosexual. Furthermore, this potency conflates with the placement of the nude male torso in opposition to the African statue, setting up a dialogic between race and sexuality. In the interiority of Woodridge’s private apartment, these two objects cohere with one another, yet when someone exterior to his dwelling witnesses the art pieces, they are read as being at odds, if based on nothing else than their sheer acknowledgement by “Invisible.” What is curious about their arrangement is the description of the African statue as “ugly primitive.” It would appear, then, that the statues signify the limited spaces of cohesion for race and sexuality. While it is unclear what Ellison’s intent is by describing the statue this way, it seems to convey a certain inchoate quality of blackness, one that may be read in terms of its implications of race and manliness. Still, it should not be overlooked that Ellison brings “Invisible” to a specifically black queer domain as an opportunity for enlightenment.

Despite Woodridge’s capacity to enlighten, in the published text he is a marginal character of limited importance to the narrative; in the unpublished draft, he is a marginalizedprofessor whose influence on the student body is subject to administrative limitation. Nevertheless, I contend that the text locates meaning at the margins but by excluding the chapter, Ellison misses an opportunity to recover the associated sexual and racial politics of meaning from that domain. This move reflects a long and complex history of struggle with regard to integrating masculine and queer identities, and queer and black identities. Later developments in black nationalist discourse articulate this notion prominently whereby a figure like Eldridge Cleaver refers to homosexuality as a “racial death-wish,” a suicidal assault on blackness, an erasure. [6][7]

Although the full “Woodridge” chapter focuses on the dramatic encounters “Invisible” has with him, the 1952 text contains two passing mentions of the character. First, while chauffeuring Mr. Norton, Invisible is baffled by Norton’s recollection of his role in assisting the college’s founder, and the privilege of being able to visit each spring, as a “pleasant fate” (IM, 39). Thereafter, Norton wishes the same for Invisible, inspiring bewilderment at the seemingly paradoxical language: “ […] I was puzzled: How could anyone’s fate be pleasant? I had always thought of it as something painful. No one I knew spoke of it as pleasant—not even Woodridge, who made us read Greek plays” (IM, 40). Later in the text, he ponders his own choice of words following his delivery of a speech for the Brotherhood:

What had I meant by saying that I had become “more human”? Was it a phrase that I had picked up from some preceding speaker, or a slip of the tongue? . . . Perhaps it was something that Woodridge had said in the literature class back at college. I could see him vividly, half-drunk on words and full of contempt and exaltation, pacing before the blackboard chalked with quotations from Joyce and Yeats and Sean O’Casey; thin, nervous, neat, pacing as though he walked a high wire of meaning upon which no one of us would ever dare venture (IM, 347).

Invisible continues ruminating on a lecture given by Woodridge on the importance of self-determination and individualism: “The conscience of a race is the gift of its individuals who see, evaluate, record […] We create the race by creating ourselves and then to our great astonishment we will have created something far more important: We will have created a culture” (IM, 347). Significant here is Woodridge’s notion of creating the self in order to create the race versus the opposite configuration. This idea problematizes race as a monolithic formulation; Woodridge rejects the demand of homogeneity in favor of free-thinking individualism. There are certainly similarities between the presentation of Woodridge in the published and unpublished texts—particularly his radical pedagogy—but missing is the overt reference to his sexuality, an elision that gives rise to heteronormative assumption and withholds an opportunity to acknowledge the sociopolitical and epistemic value of queer subjects. Discursively, rendering Woodridge’s sexuality invisible separates it from his race, preserving the primacy of the latter in an all-too-familiar fashion of giving blackness primacy above all else.[8]

Ellison’s hyperbolic framing of black queerness, however, dislocates it from the human and situates it as a kind of monstrosity—an unknowable and indiscernible condition. His plays on traditional gender expression, with respect to masculinity, establish Woodridge as a campus “freak,” an othered figure who must not only be regulated and contained in terms of sexuality, but also in terms of the esoteric knowledge he embodies. Thus, queerness is conceptualized as a source of fear, of which Woodridge is fully aware when he states “Relax, relax. I don’t hurt little boys when they come to visit me […].” Observing Invisible’s apparent nervousness, Woodridge remarks, “I can corrupt you only in those ways for which I am paid to do so.”[9]

While many of Woodridge’s remarks refer to his status as a black queer man, in his view, the academy itself conditions its students through racist and propagandized curricula aimed at producing controllable citizens. That said, the 1952 text minimizes the role Woodridge plays in enlightening Invisible about the subversive influence of race on the academy and individual consciousness; the result of this revision produces a much narrower picture of the landscape of people who shaped Invisible’s consciousness. Ellison makes this clear through Woodridge’s outbursts when he rails against the canon:

You are an idealist and a slave. That’s why you are a good debator [sic]. You believe in the stuff. You believe in any and everything that you’re supposed to believe in. My god! You’re the perfect creation of the century. A machine-made man! . . . Forget it. Forget the books, literature, oratory—everything. They don’t mean a thing.[10]

Shortly after this, Ellison folds masculinity and gender into an already vexed conversation about race by invoking the sociological theories of Robert E. Park, which themselves troubled Ellison during his time at Tuskegee. According to Arnold Rampersad, Park and Burgess assert in their textbook Introduction to the Science of Sociology, that “while the Jew stands for idealism, the East Indian for introspection, and the Anglo-Saxon for adventure, the Negro ‘is primarily an artist, loving life for its own sake. His métier is expression rather than action. He is, so to speak, the lady among the races’” (Rampersad 77). The irony here is that if for Ellison, the queer man is effeminate, we see him explicitly deploying the queer character to question why it would not be all right to be a “lady” in this redacted chapter on Woodridge:

You study sociology? . . . Well your sociology textbook teaches that we comprise what it describes as the ‘Lady of the races’. Do you remember that? . . . Then even if the rumours [sic] about me were true, it shouldn’t cause any surprise, should it? If you belong to the lady of the races, isn’t it all right to become a ‘lady’? Come, now, debator [sic], orator, answer.[11]

Here the reader is made privy to the disturbance Woodridge initiates and embodies. As an avatar of black queerness, his sexuality seems to align with Park’s designation of the negro as the “lady among the races.” Moreover, Woodridge emasculates himself, sarcastically defending his bodily presentation of femininity. In this same exchange he exclaims, “Don’t say Sir to me!” . . . “In this room you can be a human being. Slavery is ended. Understand?”[12] This is the exchange partially retained and referenced by Invisible” in the published text (IM, 346. Woodridge’s rejection of the title “Sir” denounces the fixedness and rigidity of gender norms and the ways it is used to hierarchize bodies. This outburst suggests that Woodridge does not regard “Sir” as a benign articulation of respect, but as an assumptive assault on his right to self-determination. He is fully aware that his queerness displaces him from prescriptive masculinity and, specifically because of the American rejection of homosexuality in this moment, his racial status is also thereby undone. The characterization of this important black male figure—whose radical philosophies would shift the attitude of Invisible toward the academy, change his worldview, and set him on a path of liberation from indoctrination by the white supremacist ideas upon which the academy (in Woodridge’s view) is built—presents a narrative challenge.[13]

The “lady of the races” has previously been discussed by Roderick Ferguson. He explores Ellison’s aversion to Park’s exclusion of African Americans from heteropatriarchal norms as articulated through Woodridge. Though Ferguson’s focus is not specifically black masculinity as a discursively intra-racial complication, he notes that Park’s feminization of the race canonizes African American cultural difference as a means of establishing white supremacist heteropatriarchal notions of American citizenship and subject humanity. Thus Park’s efforts to “otherize” African Americans through a schema of pathologizing gender differentiation are antagonized by Woodridge, a queer figure who repudiates the strategic formation of white literary canons and exclusive institutional and educational programs.[14]

Though Ellison rejected Park’s reductive view of African Americans, a clear example of the limited agency he ascribed to the black feminine manifests in his characterization of Mary Rambo. Mary helps “Invisible” after he faints while leaving the subway station. He describers her as a “big dark woman” with a “husky-voiced contralto” (IM, 246). She takes him home, nurses him back to health, and eventually provides him with lodging in her rooming house; a southern transplant and an embodiment of the mother figure, she nurtures his political potential and constantly encourages him to be a “credit to the race:” “‘It’s you young folks what’s going to make the changes,’ she said. ‘Ya’ll’s the ones. You got to lead and you got to fight and move us all on up a little higher. And I tell you something’s else, it’s the ones from the South that’s got to do it, them what knows the fire and ain’t forgot how it burns” (IM, 249-50). Mary does not specifically identify male southerners as change agents, rather she speaks of youth. Yet this exchange is of interest due to how she expresses an awareness of problems and potential solutions, even though she is not endowed any political agency beyond her supporting role.

Recognizing the importance of this support, Invisible states, “ […] Mary reminded me constantly that something was expected of me, some act of leadership, some newsworthy achievement; and I was torn between resenting her for it and loving her for the nebulous hope she kept alive.” We must not overlook the complication present in this love-hate relationship with Mary. She represents a feminized kind of cultural dependence—a lack of power—but at the same time she reifies the perceived necessity of the masculine. Later, Invisible is more overt in this regard:

. . . there are many things about people like Mary that I dislike. For one thing, they seldom know where their personalities end and yours begins; they usually think in terms of “we” while I have always tended to think in terms of “me”—and that has caused some friction, even with my own family. Brother Jack and the others talked in terms of “we,” but it was a different, bigger “we.” (IM, 250)

The willingness of Invisible to accept a call to action on behalf of a racial collective issued by Brother Jack, rather than “people like Mary,” warrants greater scrutiny. The openness of Ellison’s simile here would suggest that he not explicitly addressing gender, but rather a kind of racial character. But the juxtaposition of Mary as a representative type does suggest some gender implications. Most likely, it articulates a perception of southerners as passive and subservient; characteristics stereotypically interpreted as feminine. The feminine, whether embodied as queerness or as a woman, is deemed feeble and inadequate to challenge or overthrow the white power structures at the heart of the novel’s political problems. In this stratification of agentive figuration, Invisible is also more receptive to directives from a male figure than those from a woman, keeping a tight restrictive grip on a certain kind of agency which may be read as gendered or raced.

Brother Jack’s whiteness assigns a greater degree of potency to that racial category. The extent to which we may read Invisible’s interiority as reflective of Ellison’s own is uncertain, but the characterization here articulates an important typological diminishment of black agency that falls within the parameters of readings of race and gender in the novel. This racial aspect presents an even deeper problem because, with relation to formulations of masculinity, it tacitly privileges white male authority. Invisible does not go any further in unpacking precisely why Brother Jack’s “we” is different from said grouping by “people like Mary,” but clearly there is a greater degree of agency assigned to white manhood. This brings us back to the limitations placed upon Woodridge, who embodies the black and the feminine, and is subject to homophobia/misogyny and racial restriction.[15]

III

One theory that allows us to better understand the politics of masculinity that undergird Ellison’s characterization of Woodridge is Sigmund Freud’s theory of castration. Through that lens, we may also understand the intersection of race and gender that positions the feminine (and women) as disempowered and thereby of less social and novelistic importance than that which constitutes the masculine.

According to Freud, the castration complex develops in boys as a result of misrecognition of the female body as neutered and thereby lacking in potency.[16] The simplest summation of the theory explains that having deemed the male child’s burgeoning sexuality and/or relationship to the mother-figure problematic, the father may figuratively “remove” the male child’s penis to preserve his own empowered status. At the symbolic level, the theory articulates an overwhelming phallocentric concern for power and dominance, a concern that might be generative to castrate or be castrated psychically. An example of this is the encounter Invisible has with Young Emerson, a queer son of one of the trustees at the college Invisible previously attended. Barbara Foley asserts that “[c]astration and homosexuality were clearly much on Ellison’s mind [when] his protagonist approach[ed] his first major moment of recognition” (Foley, 205). This is apparent as of a copy of Freud’s Totem and Taboo sits on Emerson’s desk when the two meet (IM, 177). Foley contends that Emerson’s desire to help “Invisible” is motivated by an Oedipus complex, a theory wherein Freud argues father antagonism turns sons (sometimes violently) against their fathers in an effort to possess their mothers. According to Foley, “ […] young Emerson, who is undergoing Freudian psychoanalysis, realizes that his homosexual orientation enacts his rejection of identity with his father; his desire to help the invisible man signals his attempt at an alternative identification, as well as a belief that, as a ‘neurotic,’ he can bond with the ‘savage’ sitting across his desk” (206). Young Emerson’s investment in psychoanalysis suggests a recognition of his status as a castrated subject by way of his homosexuality. That same approach to queer identity may be applied to the characterization of Woodridge.

The non-sexualized references to Woodridge in the published text are a counterpoint to the virile way Ellison characterizes Young Emerson. Emerson looks Invisible up and down then overtly makes a remark about his body: “You have the build […] You’d probably make an excellent sprinter.” And, while the two are talking, he tangentially asks, “By the way, have you ever been to the Club Calamus?” (IM, 182). This is likely a nod to Walt Whitman’s “Calamus” poems, widely read as expressive of his ideas about homosexuality.[17] That said, Club Calamus is probably a queer gathering space. Emerson is probing Invisible to determine if he is queer. Later, he invites him to the club that evening, but Invisible declines. The question this raises regards the retention of the queer aspects of Emerson while Woodridge’s sexuality is lost. Whether this was Ellison’s decision or an editorial demand, it is significant that Ellison retained Woodridge’s presence, but not his sexuality. In terms of race representation, this contrast suggests that the stakes of black queer presentation are simply different—in the world and in the novel—than white queer presentation. It is also important to mention that at the time of publication, anti-homosexual sentiment was gaining considerable discursive traction. In part, this is evidenced by the 1952 publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which classified homosexuality as a mental disorder. This is to some degree reflective of the kind of ethos into which the novel emerges. As such, it raises the stakes regarding racial representation in a novel that aims to highlight visibility, even if it makes certain marginalized bodies further invisible.

Reading the novel in terms of its treatment of gender and sexuality helps us to better understand that Woodridge is not just a dangerous and wicked man in the world of the novel; he has, at times, been viewed as such in the world that reads the novel. In the aforementioned dialogue between “Invisible” and Woodridge, he asks, “ […] if the rumours about me were true, it shouldn’t cause any surprise should it? If you belong to the lady of the races, isn’t it all [sic] right to become a lady?”[18] This question seems to be answered by the absence of Woodridge—the instantiation of an invisible man.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] During Ellison’s years at Tuskegee, he was harassed by registrar and dean of men who at one point pressured him to exchange sexual favors for permission to leave campus during the summer for a week. This encounter with a homosexual administrator could be reimagined via Woodridge (SL, 19) .

[2] See Arnold Rampersad, Ralph Ellison: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 2007), 559.

[3] Part 1: Box 1: 146, F.16, 166, REP.

[4] Ibid., 164.

[5] Ibid., 163.

[6] See Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Ice (New York: Delta, 1968), 102.

[7] Arnold Rampersad argues that Ellison generally rejected notions of essentialism, whether in reference to Park’s and Burgess’s “Lady of the Races” theory or Black Nationalist discourse. See Rampersad,78.

[8] Marlon Riggs takes up this notion in his 1995 documentary Black is… Black Ain’t (California: Signifyin’ Works, 1995).

[9] Part 1: Box 1: 146, F.16, 164, REP.

[10] Ibid., 166-67.

[11] Ibid., 167.

[12] Ibid., 166.

[13] Following his encounter with Woodridge, “Invisible” remarks, “I wandered about in a daze. It was as though I was seeing the campus for the first time. What was to happen to me? They couldn’t send me away like this.” Part 1: Box 1: 146, F.16, 163, REP.

[14] See Roderick A. Ferguson, Aberrations in Black (Minneapolis, MN: U of Minnesota P, 2004) 54-81.

[15] Of additional interest to readings of Ellison’s characterization of black women as lacking in agency are the prostitutes at the Golden Day brothel (Edna, Charlene, and Hester), and the wife and daughter of Jim Trueblood (Kate and Matty Lou). Similar to Mary, these are women with limited agency. The prostitutes’ only role in the novel is providing pleasure for the men of the Golden Day; and Kate, in Jim Trueblood’s tale, is unable to stop him from molesting their daughter. Here again, the men of the novel are its powerbrokers (IM, 82-87).

[16] Sigmund Freud, “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality,” in The Freud Reader, ed. Peter Gay(New York: Norton, 1989), 271.

[17] See John Champagne, “Walt Whitman, Our Great Gay Poet?,” Journal of Homosexuality, 55.4 (2008), 648-664.

[18] Part 1: Box 1: 146, F.16, 167, REP.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.